Church of the Holy Family : Chicago’s Immigrant Cathedral

Roosevelt Road & May Street, Chicago

Church of the Holy Family

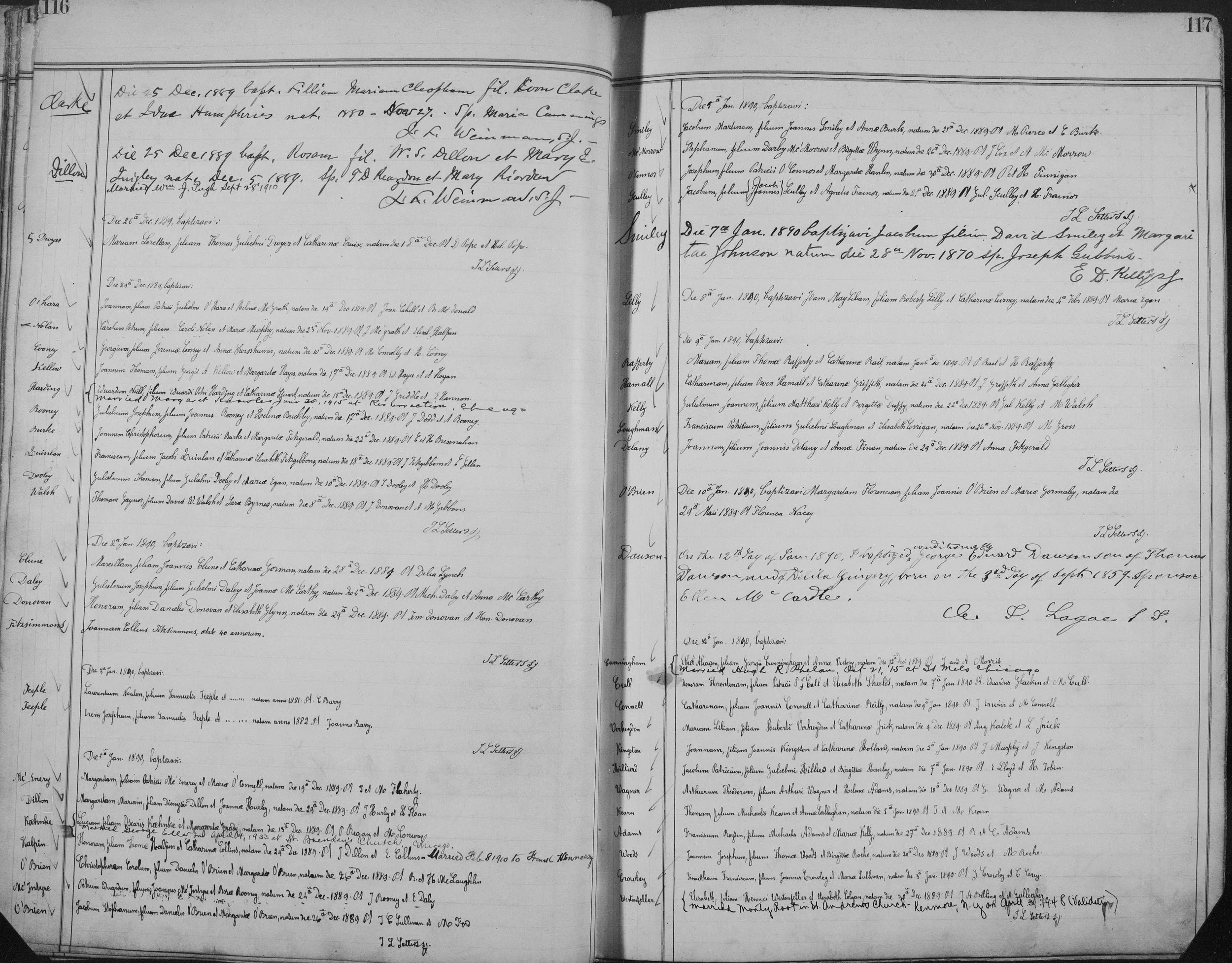

Where Owen and Catherine Hamall baptized three of their children in the 1880s—including the record that solved a seven-year genealogical mystery about Owen's half-brother William Thornton.

Churches of the Hamall Family

The Hamall family's movement through four Chicago parishes over thirteen years traces their residential mobility and community connections across the Near West Side and into Pilsen.

Thomas Henry (1880)

Mary (1885) • Katie (1890)

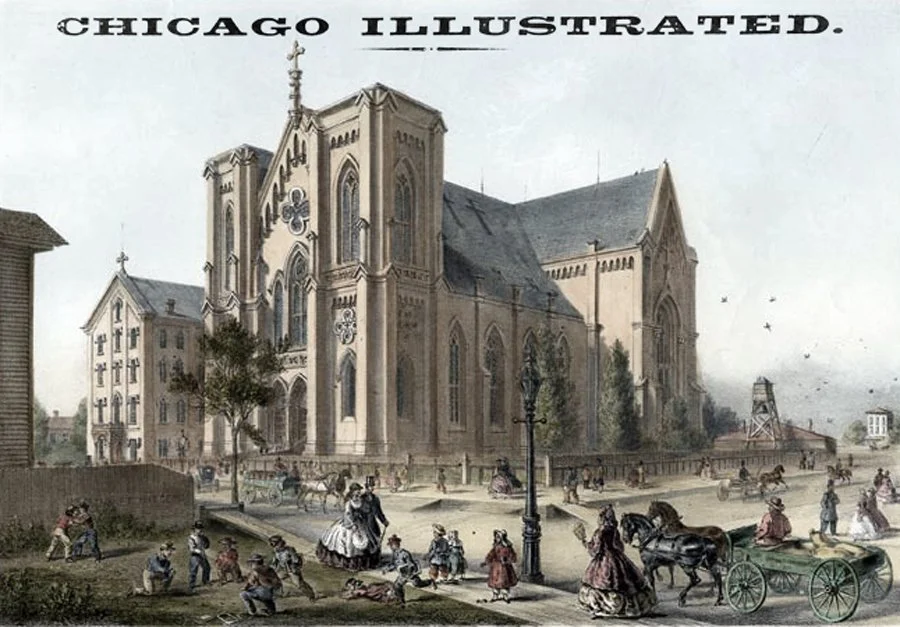

Church of the Holy Family, prior to street improvements. The 226-foot tower, completed in 1874, was the tallest structure in Chicago until the Monadnock Building rose in 1890.

Standing at the corner of Roosevelt Road and May Street in Chicago, the Church of the Holy Family has witnessed nearly 170 years of immigrant history. Founded by Father Arnold Damen, S.J. in 1857—in the midst of a financial panic—this Gothic cathedral was built with the nickels and dimes of poor Irish immigrants who had fled the devastation of the Great Famine just a decade earlier.

Among those immigrants were Owen Hamall and his family, who would make Holy Family their spiritual home in the 1880s. Three of Owen's children—William, Mary, and Catherine (Katie)—were baptized within these walls, leaving behind records that would prove crucial to solving a seven-year genealogical mystery more than a century later.

"It's estimated that one-third of Chicago's Irish trace their roots to Church of the Holy Family."

A Parish for the Ages

When the Church of the Holy Family was dedicated on August 26, 1860, it represented the hopes and aspirations of Chicago's rapidly growing Irish immigrant community. Six Roman Catholic bishops participated in the grand dedication ceremonies, signaling the importance of this new parish to the American Catholic Church.

Church of the Holy Family as depicted in Chicago Illustrated, March 1866. The bustling street scene shows horse-drawn carriages and pedestrians in period dress. The church's Gothic architecture dominated the southwest quarter of the city.

The church's architecture tells its own story. Designed by Dillenburg and Zucker for the exterior, with the interior crafted by John Mills Van Osdel—Chicago's first registered architect—the building is the city's only surviving example of pre-Civil War Victorian Gothic architecture. The structure measures 85 feet wide at the front, 206 feet deep, and 125 feet across the transept, with an interior height of 61 feet. Built of Illinois cut stone, it presented what contemporary accounts described as "a massive and imposing appearance."

At its peak, Holy Family served 25,000 parishioners, making it the largest English-speaking parish in the United States. Father Damen estimated that 18,000 persons attended service every Sunday—more than attended any fifteen Protestant churches in the city combined. The children's Sunday service alone drew 4,000 young parishioners.

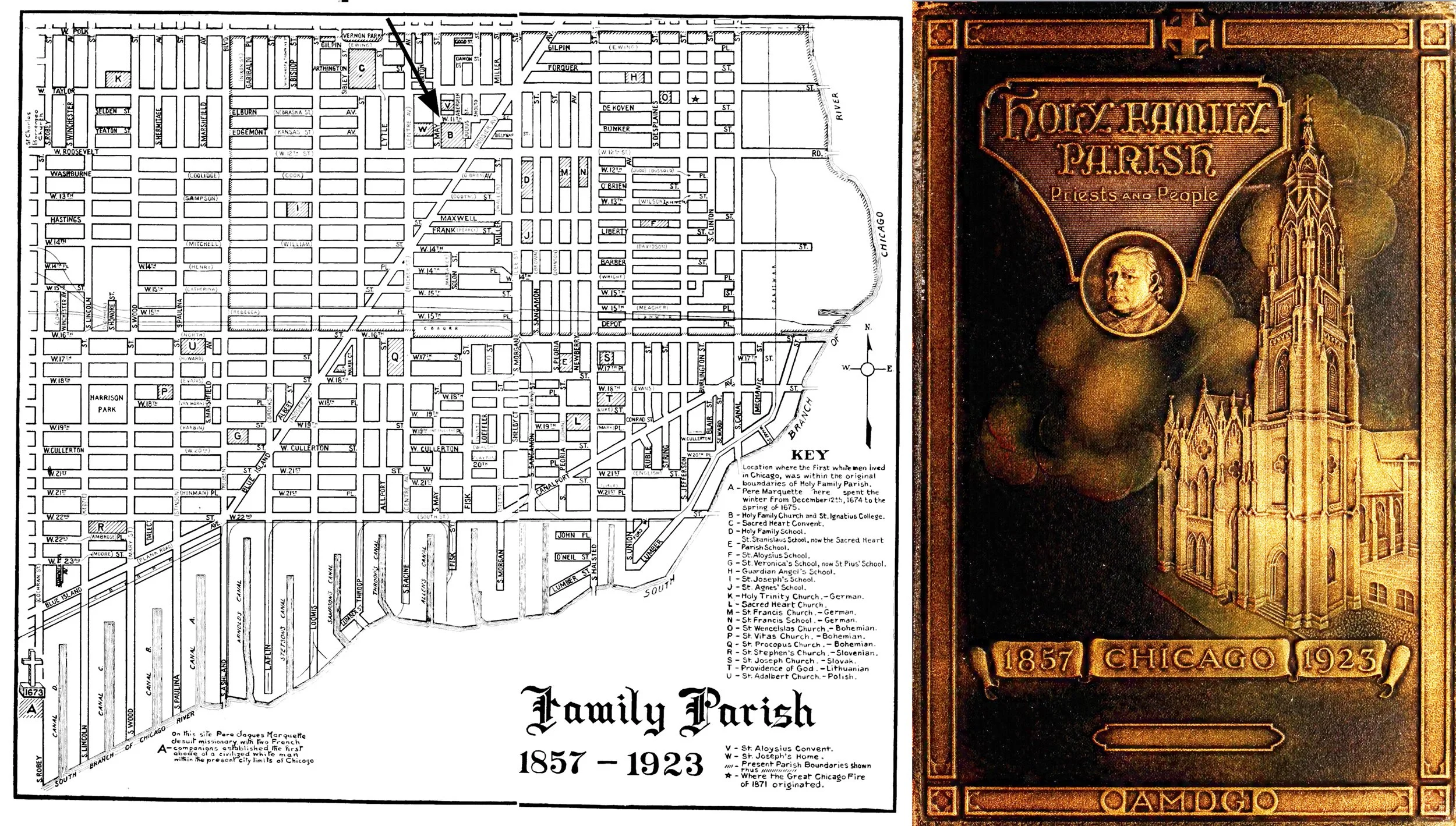

Left: Map of Holy Family Parish boundaries, 1857–1923, showing the extensive network of schools and institutions. The parish once extended from the south branch of the Chicago River west to Austin Boulevard—nearly seven miles. Right: Cover of Holy Family Parish: Priests and People, 1857–1923.

Surviving the Great Fire

The Church of the Holy Family is one of only five public buildings to survive the Great Chicago Fire of October 1871. According to parish legend, on the night the fire began, Father Damen was in Brooklyn, New York, preaching a mission at Saint Patrick's Church. When he received an urgent telegram that a major fire had started in parishioners Patrick and Catherine O'Leary's barn—just a few blocks east of the church—he prayed all night.

Father Damen pledged that if the church and his parishioners' homes were spared, he would create a shrine to Our Lady of Perpetual Help where seven candles would burn forever. The wind shifted, most of Chicago burned to the ground, but Holy Family and St. Ignatius College survived. Father Damen kept his promise. To this day, the seven candles burn in the east transept of the church.

The O'Learys themselves were Holy Family parishioners. Between 1860 and 1866, three O'Leary children were baptized in the church: Cornelius (1860), James (1863), and Catherine (1866). The family lived at 137 De Koven Street—now 537 under the city's 1909 numbering system—the site of the Chicago Fire Academy today.

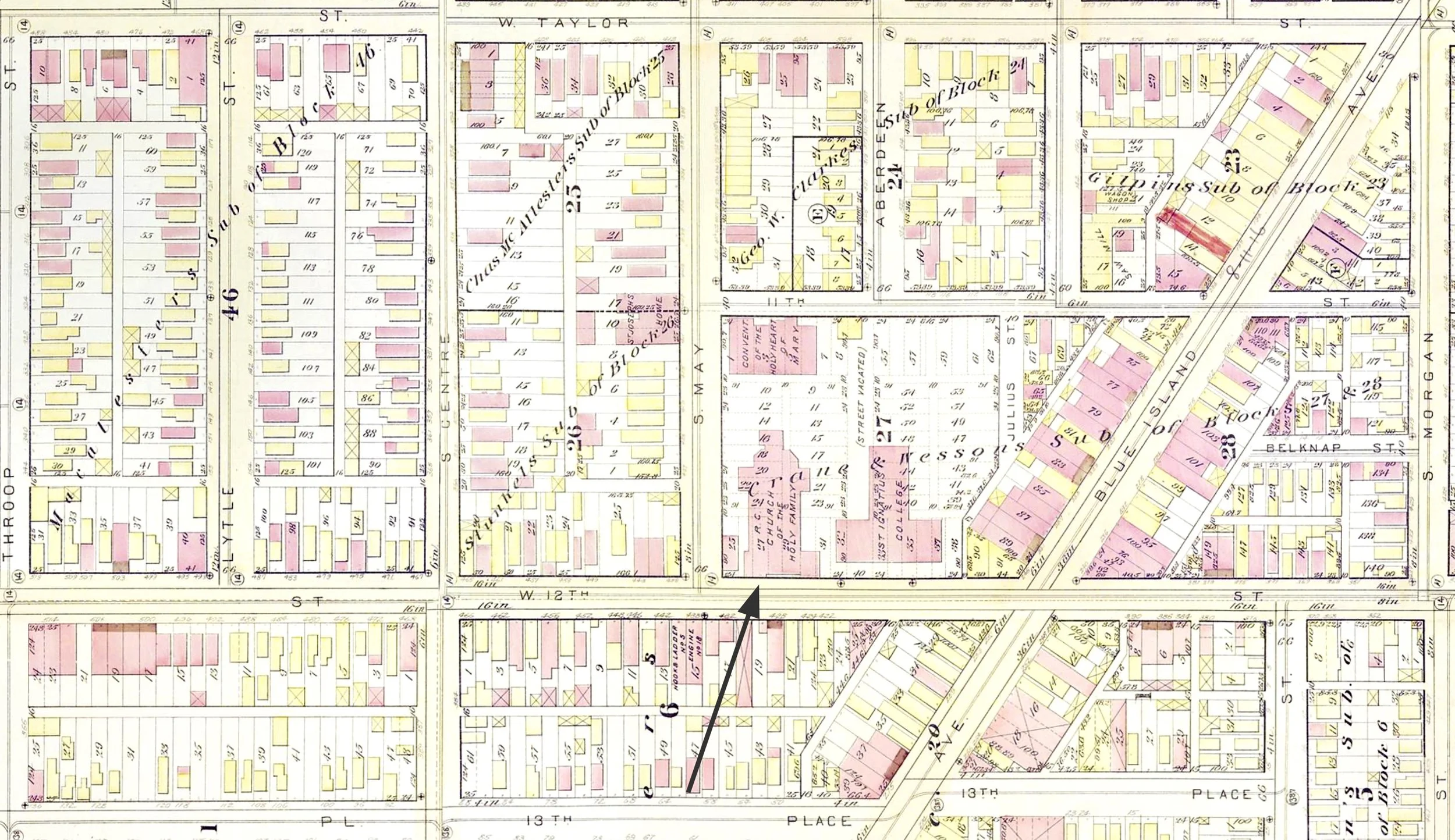

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1886, showing the Church of the Holy Family complex at the intersection of W. 12th Street (now Roosevelt Road) and May Street. The map details the dense urban neighborhood where immigrant families like the Hamalls made their homes.

The Hamall Family at Holy Family

Owen Hamall arrived in America from County Monaghan, Ireland, around 1850, part of the massive wave of Famine-era immigration. By the 1880s, Owen and his wife Catherine (née Griffith) were raising their family on the Near West Side of Chicago, within the boundaries of Holy Family Parish.

For genealogists researching Irish immigrant families, understanding parish choices is crucial. In 1880s Chicago, Catholics were encouraged to attend their local territorial parish, but families often had reasons for selecting particular churches. Residential mobility meant families frequently moved within the city for better housing or closer proximity to work. Some parishes served specific immigrant groups, while others were preferred for their schools or connections to particular priests.

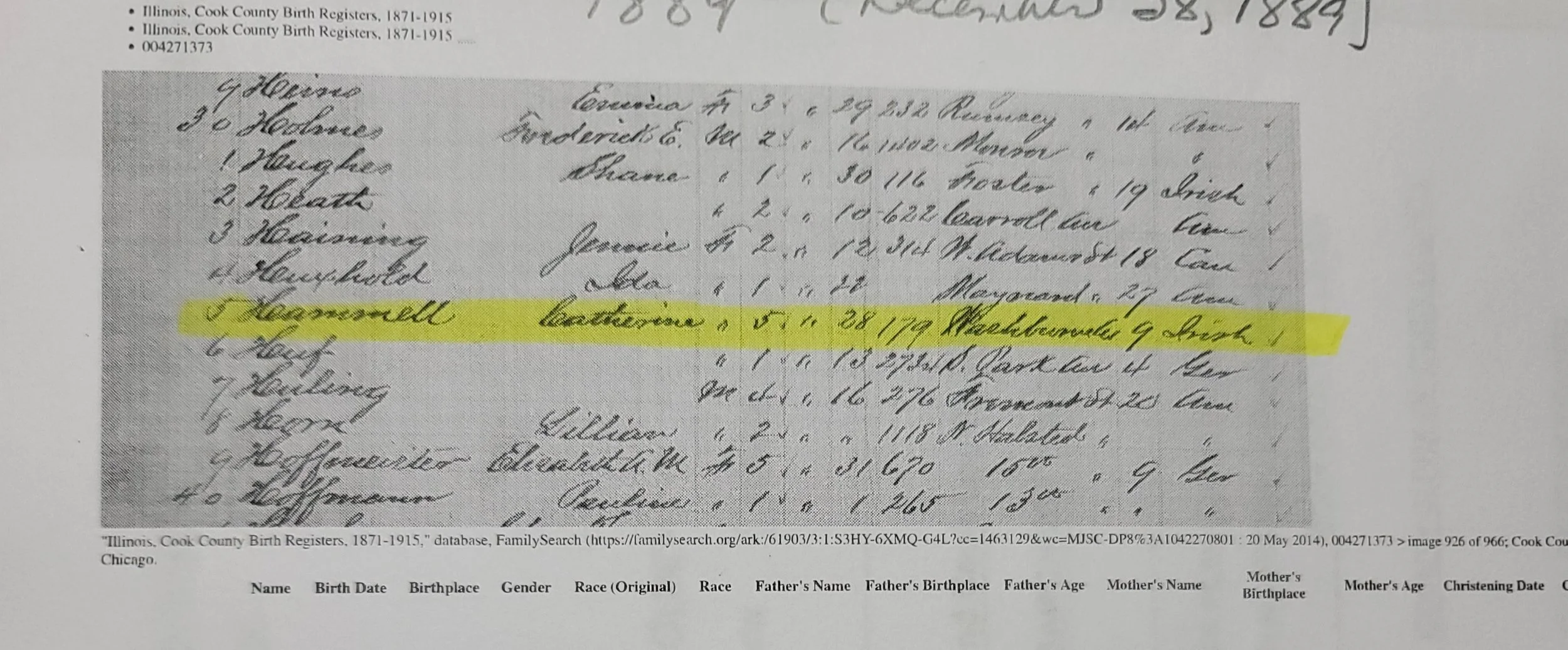

The Hamall family's movement between Holy Name Cathedral (1879–1880) and Holy Family Church (1883–1890) likely reflects their residential moves within the city. City directories and birth registers confirm the family lived at multiple addresses throughout the decade: 634 West 14th Street in 1883, and 179 Washburne Avenue by 1889.

Hamall Children Baptized at Holy Family

Sponsors: William Thornton, Elizabeth Griffith

Sponsors: M. Hammell, A. McGoubin

Sponsors: T. Griffith, Anna Gallagher

Breakthrough Discovery

The most significant of the Hamall baptismal records at Holy Family proved to be that of William, baptized January 25, 1883. The sponsor listed—William Thornton—solved a seven-year genealogical mystery about a young man with a different surname living in Owen Hamall's household in 1880.

William Hamall

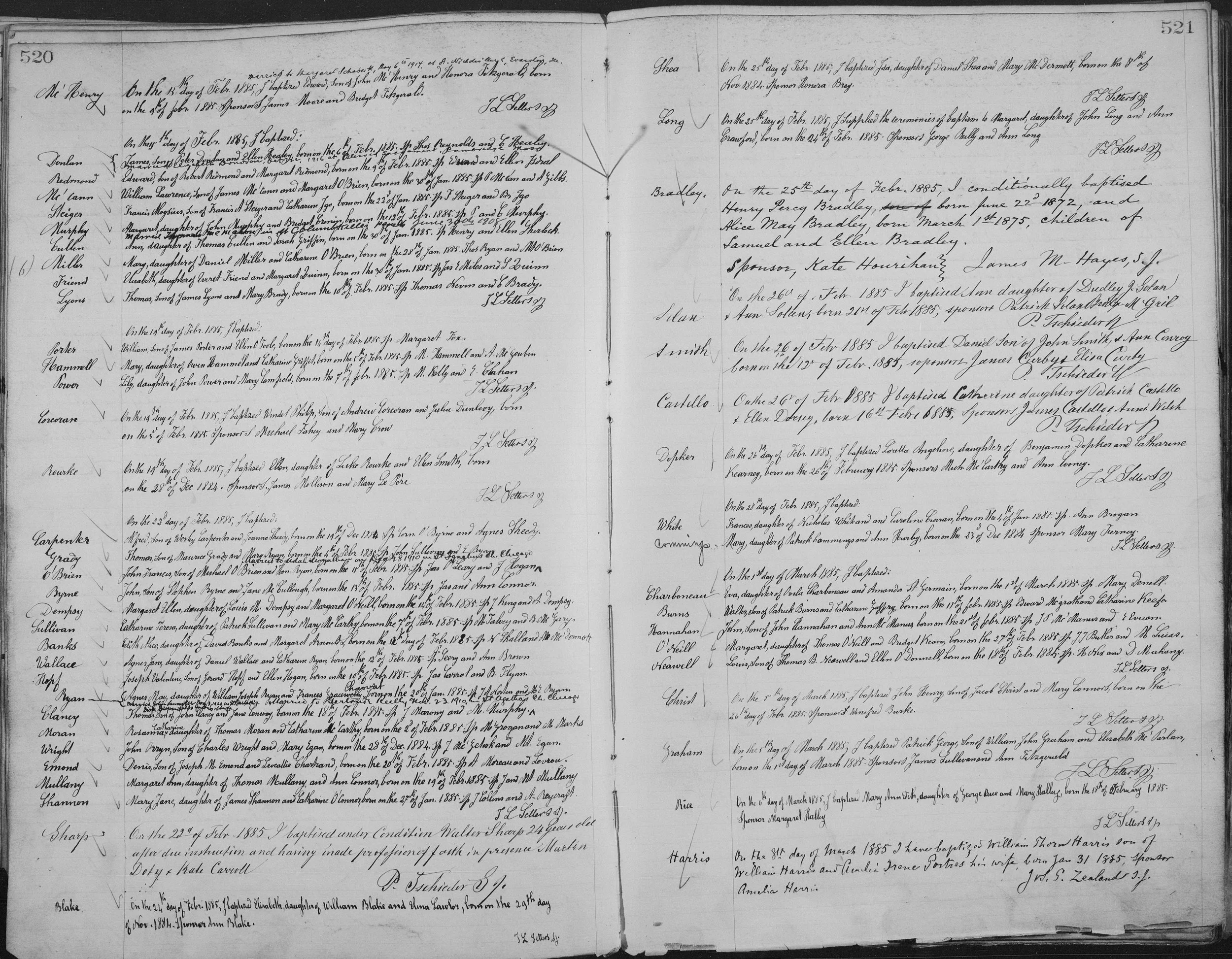

"On the 25th day of Jan 1883 I baptize William son of Eugene Hammill and Catharine Griffith Sponsors William Thornton and Elizabeth Griffith."

Baptism record for William Hamall, January 25, 1883, Church of the Holy Family. The entry clearly shows "William Thornton" as godfather—the key that unlocked the half-brother connection.

The key detail in this record is the name of the sponsor: William Thornton. In the 1880 census, a young man had been listed in Owen Hamall's household as "Hammil, Thornton"—was Thornton his first name, or was it a separate surname?

This baptismal record, combined with another discovery from the same year, provided the answer. In 1883, Owen Hamall served as godfather to Mary Thornton, daughter of William Thornton. The reciprocal sponsorship—William Thornton sponsoring Owen's son, Owen sponsoring William Thornton's daughter—demonstrates the close family relationship between the two men.

Further research confirmed that William Thornton was Owen Hamall's half-brother, born to Owen's mother Mary McMahon after her remarriage to Patrick Thornton in Montreal around 1855. This discovery connected two seemingly unrelated family lines and explained why a young man with a different surname had been living with Owen's family in 1880.

Cook County Birth Register, January 1883, showing William Hamall born January 16, 1883, to Owen Hamniell [Hamall] and Katharine Griffith. Address: 634 West 14th Street.

Mary Hamall

Daughter of Owen Hammell and Catharine Griffith. Mary would be one of only two of Owen's children to survive to adulthood, living until 1959 as Mary Hamall Holland.

Baptism register page from Church of the Holy Family, February 1885. The Hammell entry records Mary's baptism on February 19, 1885.

Catherine (Katie) Hamall

Born December 28, 1889 at 179 Washburne Avenue. Sadly, Katie would not survive childhood and is believed to be among the "lost children" of Owen Hamall.

The Church Today

The Church of the Holy Family has survived the Great Chicago Fire, depressions, shifts in population, urban renewal, and—in 1990—the threat of demolition. When the Chicago Province of the Society of Jesus announced plans to tear down the deteriorating structure, parishioners launched a campaign that raised over $1 million by December 31, 1990, saving what the Chicago Tribune called "the miracle of Roosevelt Road."

Today, the seven candles of Father Damen continue to burn. The church stands as a beacon of Jesuit faith, service, and education, partnering with St. Ignatius College Prep to serve future generations. The baptismal records that document the Hamall children's christenings—along with tens of thousands of others—remain preserved in the Archdiocese of Chicago Archives, waiting to tell their stories to researchers seeking to understand Chicago's immigrant past.

For genealogists, Holy Family's records offer more than names and dates. They reveal the intricate web of family relationships, godparent choices, and community connections that defined immigrant life in 19th-century Chicago. In the case of the Hamall family, a single baptismal sponsorship entry proved to be the key that unlocked a seven-year mystery—connecting half-brothers across generations and continents, and bringing a family story back from the brink of being lost forever.

Document Gallery

Want to Know When New Stories Are Published?

Subscribe to receive updates on new family history research—no spam, just meaningful stories when there's something worth sharing.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTEREvery Family Has a Story Worth Telling

Whether you're just beginning your research or ready to transform years of work into a narrative your family will treasure, I'd love to help.

LET'S TALK ABOUT YOUR FAMILY